Words are marvelous because they can work as a useful tool to explore possibilities to share with others with different views from yours.

11/26/2005

Siva's View 1: Introduction

He, after the war, got the job as a newspaperman in a major newspaper publishing company, and was in the charge of cultural matters, including Buddhism and pictures. In 1959, he won the Naoki Prize with the novel, "Owl's Castle," and began to pursue how Japan survived and what persons, especially men, lived and worked in this country. His eyes were not limited to the country, but went to Korea, China, Mongolia, and Tatars, which culturally contributed to what Japan was, and I think "is". And his concern flew to the peoples living near Lake Baikal because they have the same genes as ours according to scientific scrutiniy. Some of the peoples were thought to leave to survive to Japan.

I'm going to describe what Siva discovered in each stage of the Japanese history.

11/13/2005

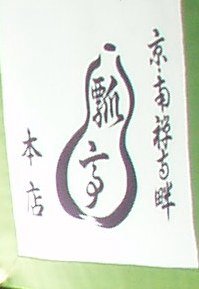

Hyotei

I went to one of the greatest traditional Japanese restaurants in Kyoto, the oldest city in Japan, named "Hyoutei." I'll describe how I ate marvelous dishes.

The first dishes were here.

The one over there is raw fish, Tai, one of the valuable fishes in Kyoto, while the one closer to you is a kind of salada with vinegar, full of matsutake, one of the most expensive mushrooms in Japan, cherished for its fragrance.

Well, let me describe what is the most important part in the room. In Japanese tradition, the part below is thought to be the most sacred in the room.

It should be noted that the flowers and the ornament you see in the photo have no relation with any religion. In Japanese tea ceremony, what matters most is tranquilty with which you do everyday-things, like enjoying seeing flowers and reading words, and having meals, and you're expected to do those things very beautifully there. By the time you pass away, you will have taken so many meals; however, you're required to cherish just one meal consisting of several dishes each of which has been elaborately cooked with so much care.

This is "dobin-mushi," which is explained in a book written by an American who is interested in Japanese cuisine, "delicate clear soup made in an individual miniature dobin ... [or] a famous autumn speciality of Kyoto and usually contains matsutake, chicken, mitsuba, and ginnan. The juice of sudachi is squeezed into the dashi, which is drunk from little cups. The other ingredients are fished out chopsticks and eaten. One of the great delicacies of Japan."

This is "dobin-mushi," which is explained in a book written by an American who is interested in Japanese cuisine, "delicate clear soup made in an individual miniature dobin ... [or] a famous autumn speciality of Kyoto and usually contains matsutake, chicken, mitsuba, and ginnan. The juice of sudachi is squeezed into the dashi, which is drunk from little cups. The other ingredients are fished out chopsticks and eaten. One of the great delicacies of Japan."

I ate seven dishes there. A meal, consisting of the seven dishes has been regarded here as the greatest and most gorgeous meal in Japan since the twelfth century. The second greatest meal has five dishes, and the third one three dishes. The photo on the left is one of the seven dishes, which comes third. The hard-boiled egg in this restaurant is well-known for its delicateness. I would recommend you to try this if you had a chance to eat there.

The last dish is the dessert, with which I concluded my special meal in Kyoto, with tea, called "matcha".